Research

Last updated: 03 February 2026

My research mostly resides in the realm of ecology and conservation biology, with a focus on amphibians and reptiles. I am most interested in studying wildlife populations over different gradients of natural and human disturbance, and applying those relationships for understanding future threats against biodiversity and guiding conservation planning. I work with a variety of organisms and ecosystems, ranging from vernal pool amphibians to Galápagos tortoises, and use various quantitative techniques for studying ecological and demographic processes. I’m also interested in social dimensions of wildlife ecology and using historical data and social-ecological frameworks to better understand complex conservation stories.

Here is a short list of some projects I’ve worked on over the last several years.

Wildlife conservation

Left: A Tapichalaca tree frog (Hyloscirtus tapichalaca) from southern Ecuador. Right: Spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum).

Cryptic species and ecosystems

My current work at the University of Maine focuses on improving conservation capacity for cryptic species and ecosystems. Specifically, I’m working on developing new monitoring approaches for studying rare salamanders in the unisexual Ambystoma complex and forested vernal pools that remain highly vulnerable throughout their range. These species and ecosystems are both highly cryptic (i.e., they are hard to detect and distinguish) and present unique challenges to researchers, managers, and conservation stakeholders.

Working with a team of collaborators in academia and government, I am exploring the potential of innovative trapping approaches and environmental DNA (eDNA) for detecting rare species in vernal pools, identifying critical habitat, and characterizing pool biodiversity over large spatial and temporal scales.

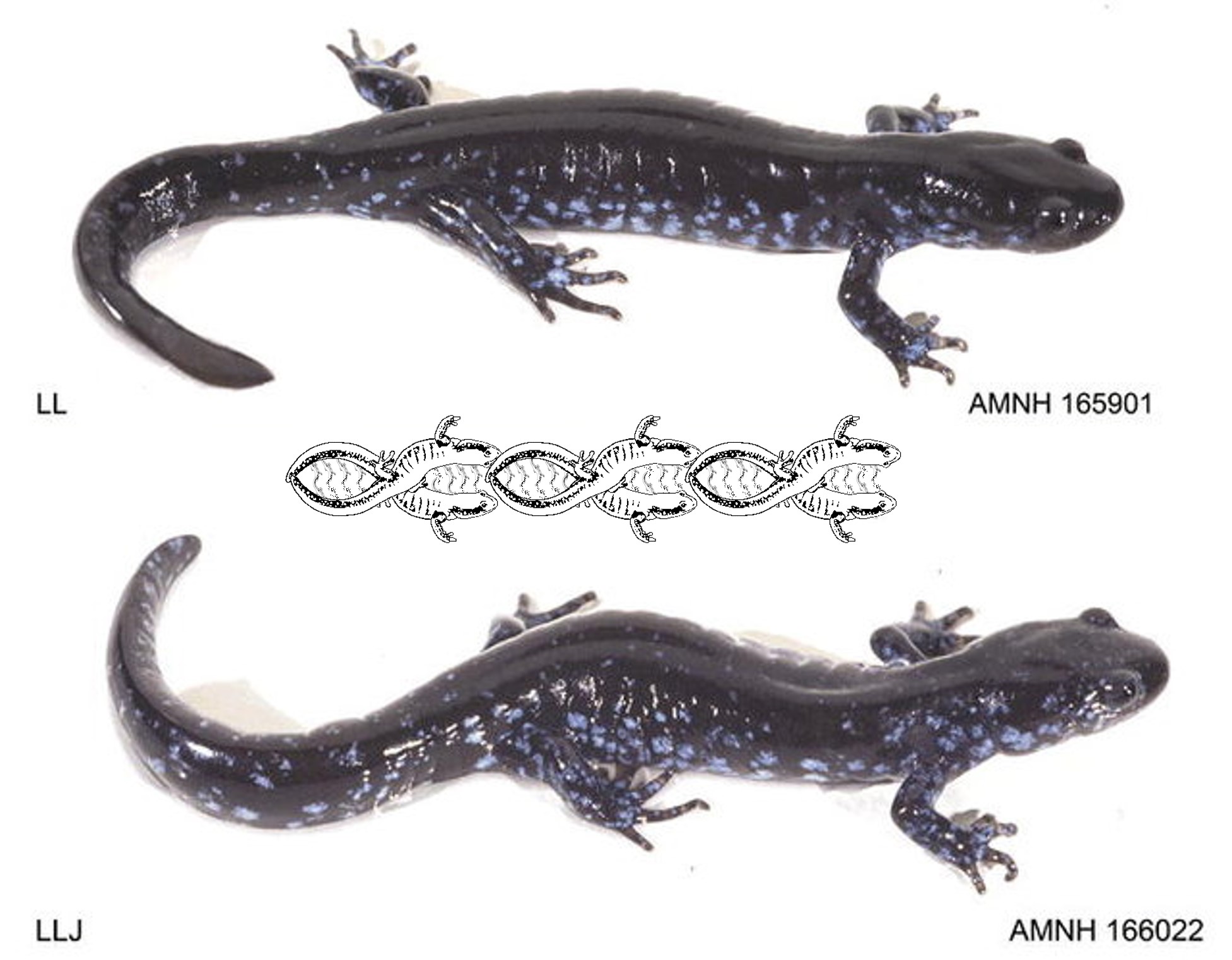

Blue-spotted salamanders (top) and unisexual Ambystoma. Image from Bogart & Klemens (2008).

Relevant literature:

Goldspiel HB, Davis SK, Winiarski EC, Kubel JE, Grey EK, Charney ND. Accepted. Detection and succession properties of forested vernal pools with eDNA metabarcoding. Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

Goldspiel HB, Charney, ND. 2025. Ambystoma laterale-jeffersonianum complex (Unisexual Ambystoma). Polydactyly. Herpetological Review. 56.2: 175-176. PDF

Goldspiel HB. 2025. Edna and Al. Spire: The Maine Journal of Conservation and Sustainability Vol. 9.

Goldspiel HB, Hoffmann, KE, Charney, ND. 2025. Light at the end of the funnel: Taxonomic biases of aquatic funnel traps and glow sticks for studying wetland-breeding amphibians. Journal of Herpetology. 59.1: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1670/2460810

Goldspiel HB, Hoffmann, KE, Charney, ND. 2023. Ambystoma laterale-jeffersonianum complex (Unisexual Ambystoma). Longevity. Herpetological Review. 54.4: 614-615. PDF

Land-use legacies

Most forests in the eastern United States have rich histories of human disturbance, many having once been cleared for agriculture and regenerated in the last century. These landscape transformations came at a cost for wetlands, which are central to the life cycles of many frogs and salamanders. In recent decades, many landowners have taken to creating artificial wetlands as a means of restoring amphibian habitat, but these created wetlands have mixed rates of success for amphibian populations.

For my master’s thesis, I was interested in how historical landscape setting (i.e., adult habitat quality) and vernal pool densities (i.e., larval habitat availability) interactively affect the outcome of these habitat restoration projects. This work occurred at Heiberg Memorial Forest, an experimental research station operated by SUNY ESF in Tully, NY.

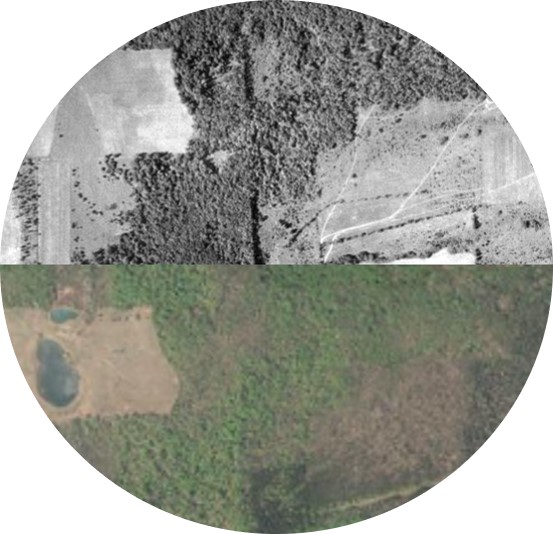

Land cover at Heiberg Memorial Forest (Tully, NY) in 1936 (top) and 2015 (bottom).

Relevant literature:

Goldspiel HB 2018. “Forest Legacy Effects on Amphibian Populations: Integrating Land and Life Histories in Conservation” (2018). Dissertations and Theses. 40. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds/40

Goldspiel HB, Cohen JB, McGee GG, Gibbs JP. 2019. Forest land-use history affects outcomes of habitat augmentation for amphibian conservation. Global Ecology and Conservation 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00686

Media: The Wildlife Society

Island rewilding

From 2018–2020, I worked with Galapagos Conservancy’s Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative (GTRI), providing analytical support for long-term demographic and ecological data on tortoises and islands in the Galápagos archipelago.

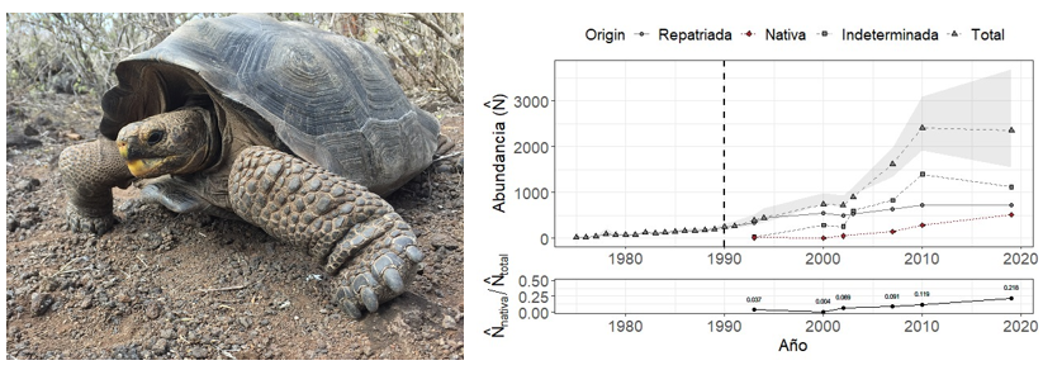

Population regeneration of giant tortoises on Española following 50 years of captive breeding and repatriation.

Once numbered in the hundreds of thousands throughout the archipelago, Galápagos tortoises have suffered extreme population declines and extinctions over hundreds of years due to human activity. GTRI works together with the Galápagos National Park Directorate to restore tortoise populations to their historical ranges and sizes, via research, captive breeding, and management programs.

Relevant literature:

Tapia, WA, Goldspiel, HB, Gibbs, JP. 2022. Introduction of giant tortoises as a replacement “ecosystem engineer” to facilitate restoration of Santa Fe Island, Galapagos. Restoration Ecology: e13476. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13476

Tapia, WA, Goldspiel, HB, Sevilla, C, Málaga J, Gibbs, JP. 2020. Santa Fe Island: Return of Tortoises via a Replacement Species. In: Gibbs, JP, Cayot, L, Tapia, WA, editors. Galapagos Tortoises, 1st Edition. Academic Press, Cambridge, MA.

Gibbs, JP and Goldspiel, HB. 2020. Population Biology. In: Gibbs, JP, Cayot, L, Tapia, WA, editors. Galapagos Tortoises, 1st Edition. Academic Press, Cambridge, MA.

Media: NY Times, The Guardian, The Daily Show, Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me

Biotechnology

With rapid advancements in transgenic research, biotechnology has become more commonplace in discussions about ecological restoration. These techniques present numerous opportunities for conservation, as well as numerous uncertainties about potential non-target effects on other organisms. Following decades of research at SUNY ESF with the American Chestnut Project, American chestnut (Castanea dentata) has become a primary case study of species restoration using biotechnology. As part of the regulatory approval process for planting these trees, various studies have been done to examine non-target effects on native species and ecological processes. Until 2017, no research had yet been conducted to examine potential effects of transgenic plants on forest-dwelling vertebrates, such as amphibians. In collaboration with the American Chestnut Project, I conducted a lab survival experiment to study interactions between transgenic American chestnut litter and amphibian larvae.

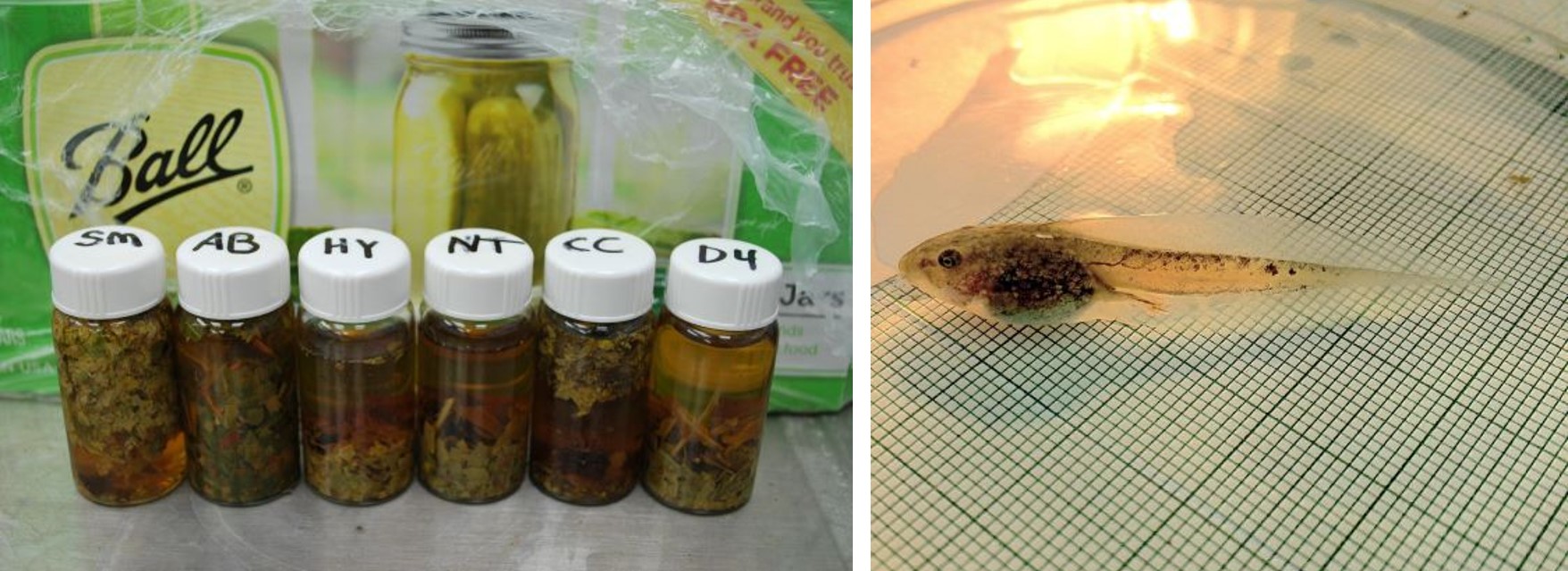

Left: Sample vials of leaf litter with pond water from central New York. Right: a wood frog (Lithobates sylvaticus) tadpole.

Relevant literature:

- Goldspiel HB, Newhouse AE, Powell WA, Gibbs JP. 2018. Effects of transgenic American chestnut leaf litter on growth and survival of wood frog larvae. Restoration Ecology: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12879

Media: Pacific Standard

Compiled in R with RMarkdown and Github Pages.

Copyright © Harrison Goldspiel.

Social media and forest recreation

Project websites: ESF, NSRC

Vignettes: Point pattern analysis, Flickr tag mapping

Relevant literature:

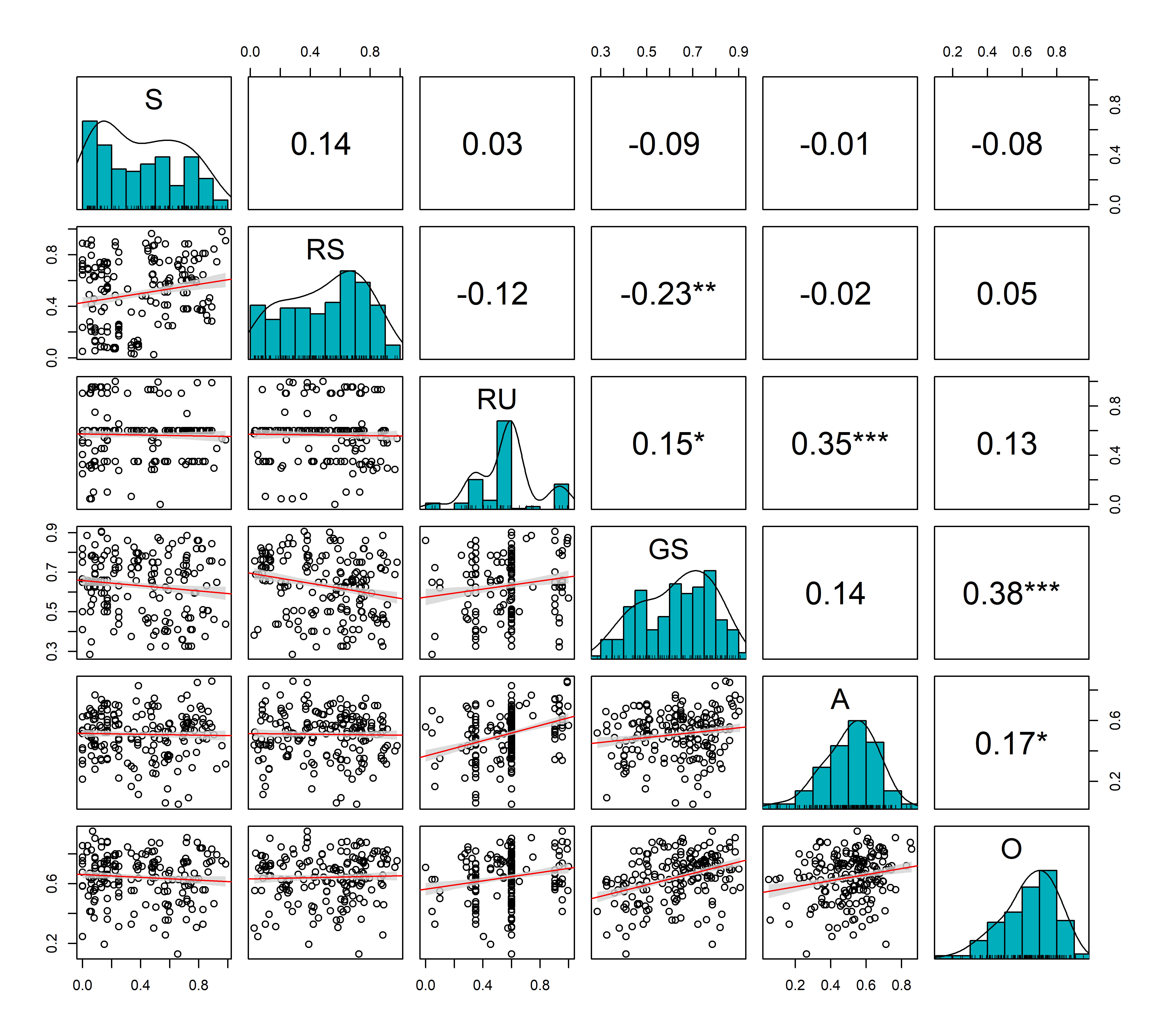

Goldspiel HB, Barr B, Badding J, Kuehn D. 2023. Snapshots of Nature-Based Recreation Across Rural Landscapes: Insights from Geotagged Photographs in the Northeastern United States. Environmental Management 71: 234-248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-022-01728-2

Kuehn D, Gibbs J, Goldspiel HB, Barr B, Sampson A, Moutenot M, Badding J, Stradtman L. 2020. Using Social Media Data and Park Characteristics to Understand Park Visitation. The Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 38.2: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.18666/JPRA-2019-10035